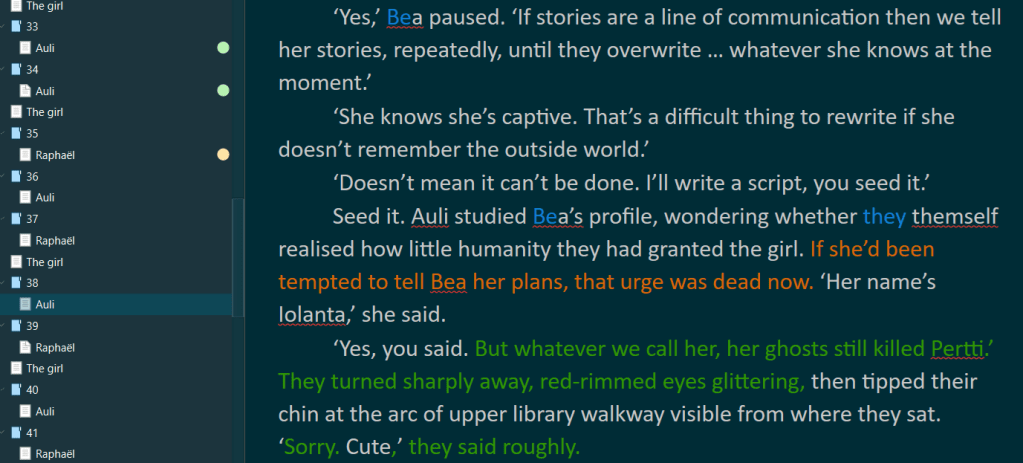

Updates from the writing cave: Since I last posted here, I have finished the first draft of the strange and challenging parallel world book that I began over the summer. I’ve done a quick first pass tidy up of it and have now shelved it to work on other things while it thinks about what it’s done. I’m really pleased to have completed such an unusually structured draft, but there’s some substantial decisions to make about what it needs next, so I’m hoping a few months of marinading will let me come back to it with fresh eyes.

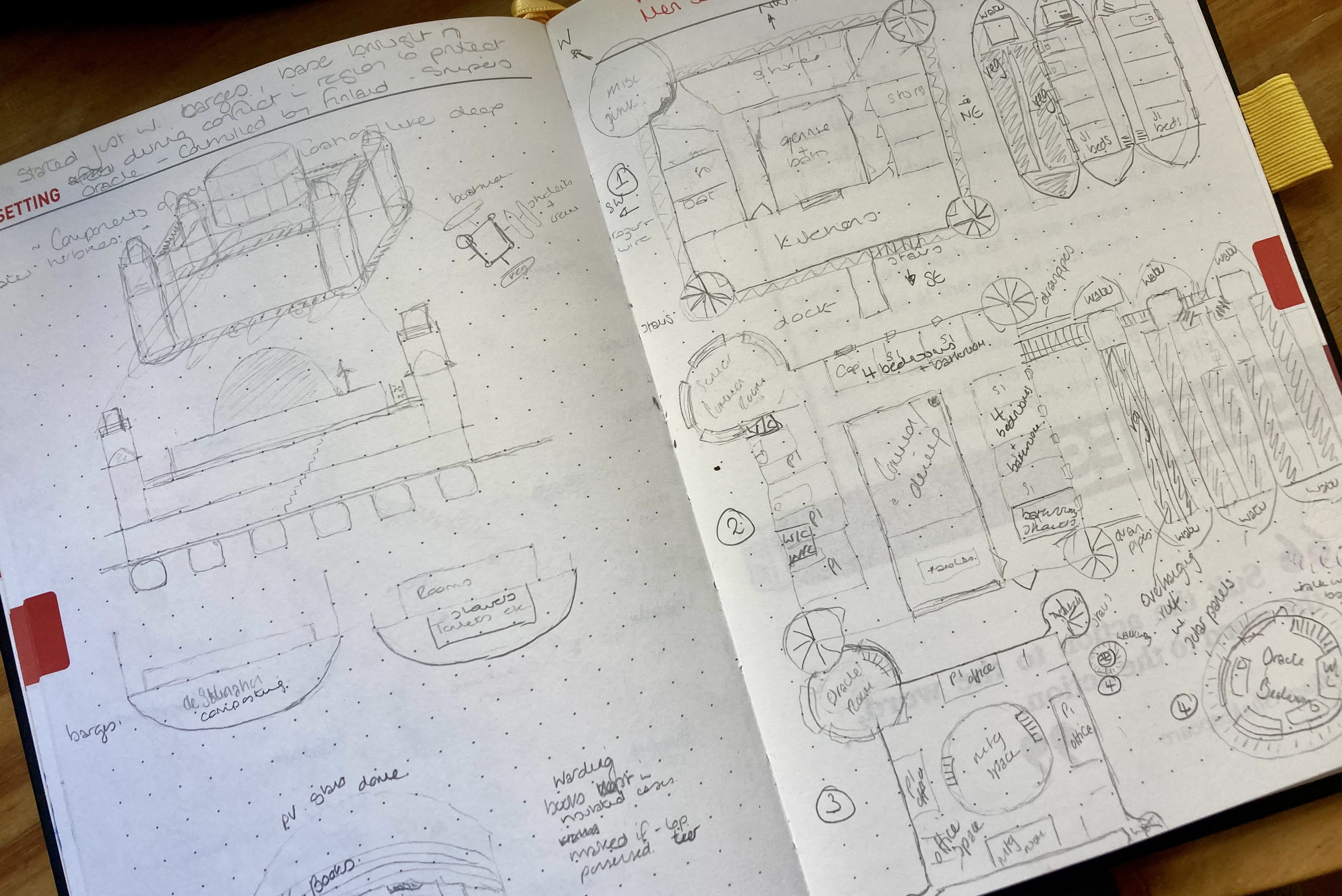

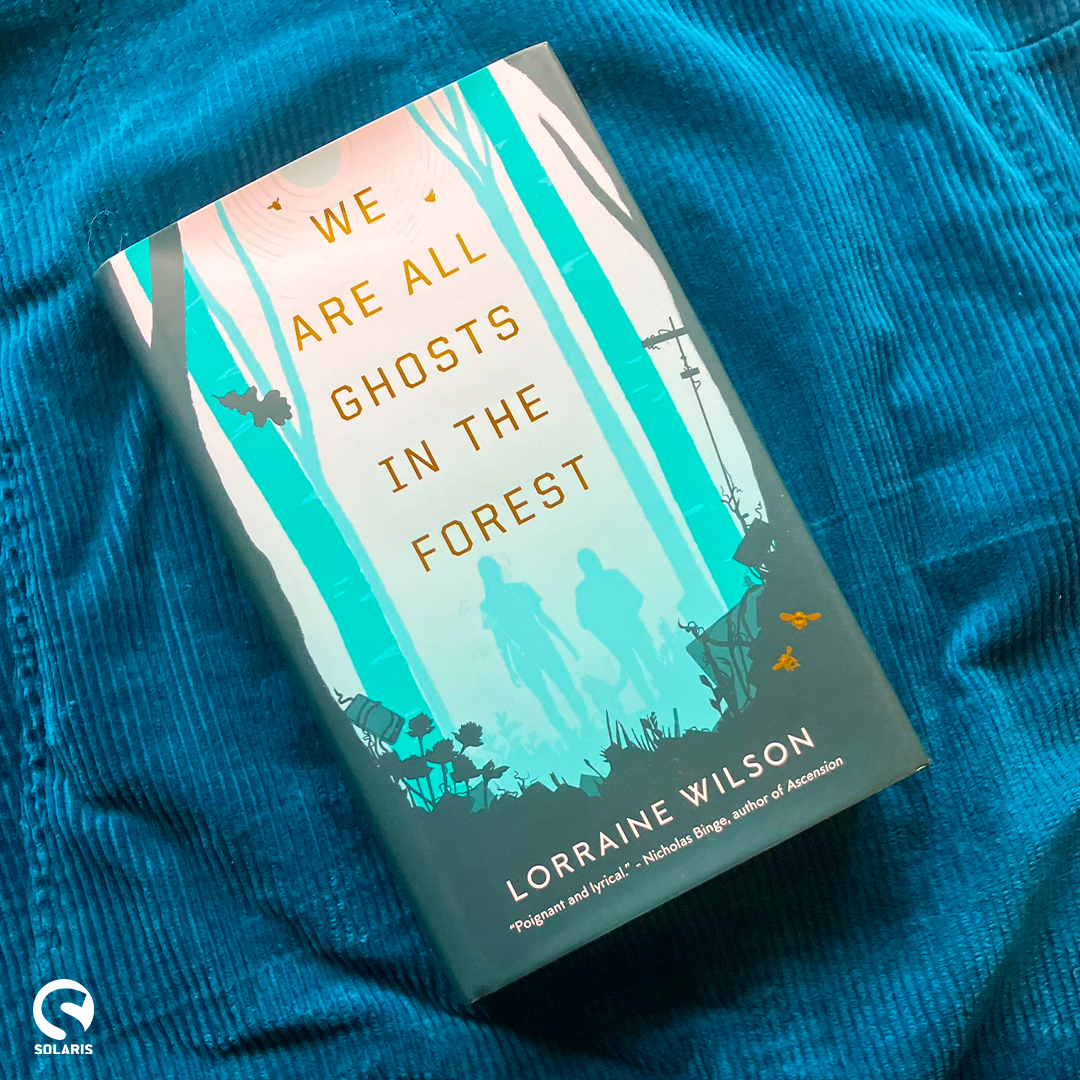

Now. If you follow me on Bluesky or Instagram, you will know that I am firmly into pre-publication promo season for The Salt Oracle (and the paperback release of We Are All Ghosts In The Forest). It’s the point in time when most authors exist in the greatest dichotomy of externally doing the chirpy promo, whilst internally dying of embarrassment, awkwardness and cringe. It’s simultaneously lovely to share your excitement with your community and uncomfortable to feel like you’re hustling. But pre-orders and early sales really do matter. And I want to give these books what small boost is within my power, so I am trying to make it as fun as possible (for me, heaven knows what’s ‘fun’ to the IG algorithm!).

These two books are out on Thurs 6th Nov – two weeks yesterday – and next Sunday I get to launch them a little early at World Fantasy Con in Brighton, alongside some splendid and talented friends, Sam K Horton and MK Hardy, celebrating their books Ragwort and The Needfire. It’ll be a fun event, with cake and arty freebies and hot-off-the-press books, so if you are in Brighton please do come find us!

For today though, I figured I’d talk about other books!

As a bit of a ‘where do your ideas come from’ post, I have gone through my shelves and notebook to give you a small sample of the many stories and scraps of science, folklore and natural history that were part of the landscape from which I developed The Salt Oracle. If you’ve been with me a while, you might remember me talking about the Dark Academia elements of this book, but it’s also fairly apparent that beyond general academia vibes, my specific experiences with marine and conservation science also fed into this story.

Though I’ve never lived on a floating college fortress, I have lived in research stations or field camps in Scotland, Eastern Europe, the Indian Ocean islands, and Central America. It’s a strange microcosm of an environment, living closely with a small, often very isolated team made up of people who might be thrown together with no prior connections, and who are working long hours in often hazardous environments. There is a strange, often fleeting but always quite intense companionship that springs up in those settings, partly out of proximity and shared interests, but partly out of a need to get along for everyone’s safety and comfort. I definitely drew on my memories of such relationships in my writing the close but occasionally downright incompatible crew in this book.

Likewise I was able to draw on the marine conservation research I’ve been a part of, that includes things like whale communication, marine mammal fisheries bycatch, coral reef health, sea turtle breeding, sea bird population modelling and conservation, etc. That research wasn’t a huge part of my academic time, but I’m lucky enough to know people who work in all walks of marine research, so I had a way in to reading up on buoy and satellite tag technology, fisheries policy, renewables deployment and so on. (My work also took me to a hotel in Stromness, Orkney, which has on the wall a radar image of the Pentland Firth showing all the German submarines sunk at the end of WWII – the tangled poignancy and hidden threat of that image stuck with me, and got a tangential reference in The Salt Oracle)

As a seven year old, I decided that I was going to ‘save the whales’. I don’t know what exactly I thought I was going to do, especially once I declared that I would do so by becoming a vet! But while I never got to save a whale, perhaps this book is my inner 7 year old channelling all her undiluted rage at what we are doing to the oceans, and wishing vengeance upon us all!

Other than an undertow of eco-rage, what else fed into the making of this book?

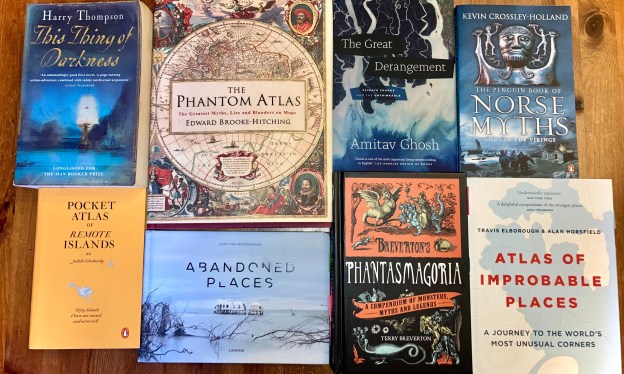

A lot of folklore, obviously. Can I write a book without it? And would I even want to? (No, and no). (If you don’t possess a copy of Breverton’s Phantasmagoria, please correct that terrible tragedy forthwith.) As you might gather from the image below, I do a lot of happy browsing through books of lost and abandoned places like I’m shopping for my retirement home/island. This is only about half the ones I own, and I highly recommend them if you are seeking inspirations for settings or mysteries or strange scraps of history. It is, incidentally, from that wee orange one in the bottom left that I read the fragment of history which gave me my setting in Mother Sea (the godawful history of the island of Tromélin).

As well as plaguing my sailing-obsessed sister for technical details, I also adore historic maritime explorer books and their wealth of perspectives on the ocean in an era when it was still so unknown and dangerous. In the picture below is the exquisite fictionalised story of Darwin’s voyages in This Thing Of Darkness – a beautiful, oddly sad and uplifting story.

Lastly for the non-fic, there are so many vital books out there now that explore climate change and our society’s responses to it. At the time of drafting The Salt Oracle, perhaps most recent read for me was this first beautiful and heartbreaking essay collection by the wonderful Amitav Ghosh.

How about fiction?

As you might expect, I am an unapologetic sucker for anything remotely Dark Academia shaped! There are issues I struggle with in this genre, and sometimes those flaws outweigh the joys of libraries! research! existential crises! but I will never not be tempted by books which centre the corrosive seduction of learnéd institutions. If We Were Villains and The Secret History are both rightly famous and need little explanation from me other than to say that while I prefer the former over the latter, I appreciate what the latter means to the whole genre. Likewise something that I really adoredabout Vita Nostra and the Scholomance series by Naomi Novik was how they both broke so entirely away from the dreaming spires, gothic architecture vibes of most DA. It’s probably fair to say those books gave me a lot more confidence when I came to writing my creaky, rusty hulk of a college!

Just as with non-fic, I am of course a fan of the many beautiful books that tackle climate change themes in interesting and nuanced ways within fiction. There are too many to list but at the time when I was formulating this book, Claire North and the great Octavia E Butler were probably top of my mental reference piles! I loved particularly how these books fold the climate themes into other forms of plot, as this was something I wanted to do (why write 1 genre when you can write 4, anyway) in The Salt Oracle.

There’s been a bit of a madcap trend in the short fiction world recently, of writing retellings or sequels to Ursula K le Guin’s famous The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas – a short story that explores the brutal cost of utopia and who is willing to pay it. Some of these recent reimaginings have… rather missed the point of the original, in my mind, so I did my usual recalcitrant teenager act of refusing to say that Omelas was one of the core inspirations behind my book. But a wonderful author friend noted it, unprompted, in their blurb, so the (not really) secret is out, and I hope readers are intrigued and satisfied with this rather tangential take on le Guin’s posed question.

Two books in the image above that perhaps aren’t so obviously connected to The Salt Oracle are Amitav Ghosh’s The Hungry Tide, and MM Kaye’s Death In The Andamans. The former is there because of the sheer beauty of his descriptions of the ocean’s liminal edge wreaking wonder and devastation in equal measure. It’s a heartbreaking book, but one climactic passage describing a terrible storm tide haunts me even now years after reading it. That vibe of awe and horror, of both the power and the powerlessness of the sea, is something that hopefully echoes in the pages of my book.

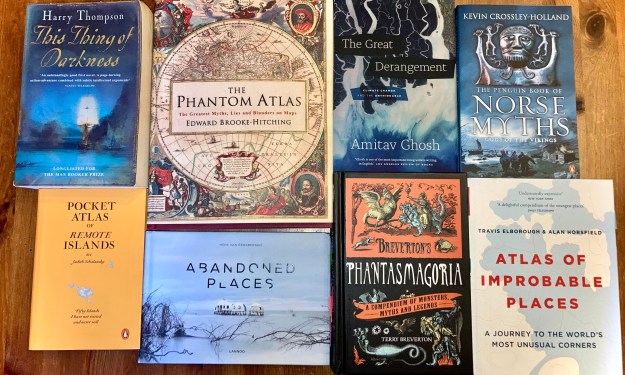

MM Kaye’s 6 murder mystery books are not the ones she’s famous for, and are definitely books ‘of their time’. But I adore them for her masterful ability to create rich, captivating settings that just ooze atmosphere and tension. In this book in particular, the key mystery events take place largely in one house, and the book includes (drumroll)… a floorplan. I am not a big fan of maps in books, but for reasons known only to the mice that occupy my brain, I adore a floorplan. Just. Perfection. Perhaps because that way I know where the library is. Anyway, as well as being a constant inspiration to me in writing atmospheric settings, MM Kaye gifted me the initial idea for the layout of the Bellwether – the college in The Salt Oracle.

And so, in case hustling on social media wasn’t mortifying enough, I’m sharing the floorplan sketches I did in my notebook for your delectation!

I am, as you are now sadly aware, not a natural artist! (also some of this changed, so don’t use it as a reference!) But this was a surprisingly essential part of my drafting process, because ooft the number of times I had to check back to see where characters ended up after running down some stairs…

A slightly random post from me today, fuelled by the dual horns of ‘I don’t want to just promo the book’ and ‘I can’t ignore the fact that it’s nearly release day’. I hope there’s some temptations in here for you, and if you pick up any of these books, or have your own strange and fascinating sources of inspiration please do let me know.

Thank you, as always for your support. Because accessibility in publishing is important to me, I keep all my craft and publishing posts free, so any shares or tips are greatly appreciated. Wishing you a fabulous weekend.